The Yield Curve is Steepening – And This is The True Signal of Trouble Ahead

Back in August, I wrote about the U.S. yield curve’s deep inversion and why it was important (read here).

I said,

“. . .This is why the U.S. yield curve is so deeply inverted. Speculators believe the Fed’s created a potentially severe recession in its pursuit to lower prices. And will be forced to reverse course and ease aggressively at some point (sooner-than-later) to save the economy. But for now – it seems like things will only worsen from here. . .”

Well – six months later – the global system is now suffering from its largest bank crisis in decades.

So, it appears the yield curve was onto something yet again.

It signaled greater fragility in the system as the Federal Reserve hiked rates at its fastest pace in decades.

(Isn’t it ironic that as the Fed fought inflation through tightening, it effectively planted the seeds for a banking crisis and recession? This is why the boom always leads to the bust.)

But I’ll take it a step further. . .

I’ve argued in the past that yield curve inversion actually helps spur a slowdown and create bank stress.

Why?

Because banks actually use the inverted yield curve as a signal for their own lending policies.

Thus when the curve inverts “even modestly,” banks tighten lending standards or increase price terms across every major loan category.

And this is exactly what we’ve seen since Q2-2022.

The net percentage of banks tightening credit standards has risen sharply across the board. From large-and-small business loans to credit cards and auto loans.

And this is data from Q1-2023 – before the Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) implosion.

Since then banks have most likely tightened even further as they’re rushing to save themselves and shore up deposits instead of loans.

This is an issue because banks are the main outlets of money creation (bank loans create deposits, which is credit in the economy).

So, what does all this mean?

Well, the yield curve is currently ‘un-inverting’ (aka steepening).

And – contrary to what the pundits say – that’s a big reason to worry. . .

The Yield Curve is Steepening – And According to History, That’s Something to Worry About

To give you some context: the U.S. yield curve has been inverted since mid-summer 2022.

This means that the long end of the curve is yielding less than the shorter end.

Why does this happen?

Putting it simply, it’s when the bond market (which controls the longer end of the curve) is at odds with the central bank (which controls the short end of the curve).

Thus inversion happens when a central bank arbitrarily forces up short-term rates (such as when the Federal Reserve lifts its discount rate). And investors instead begin pricing in a slowdown and deflation (buying the long end, which pushes yields lower).

Now, there are two real ways for the yield curve to steepen.

First: if growth and inflation begin picking up, which makes investors re-price long-term yields higher. But most often this doesn’t happen (at least in the last 40 years it hasn’t).

And second: when the Fed begins cutting rates, which happens during a liquidity crisis or recession. Lowering the spread between the short-and-long ends (this is usually what leads to steepening).

Therefore it’s not the inversion that’s the big signal (although it’s the beginning stage).

But instead, it’s when the curve begins un-inverting that signals trouble right around the corner.

“The yield curve always steepens into recession,” Bank of America’s Michael Hartnett said in a Friday note.

And that’s exactly what’s started happening since SVB blew up 10 days ago – the yield curve is now steepening.

For perspective:

1. The spread between the 10-year and 2-year is now negative 47 basis points (-0.42%) vs. negative 107 (-1.07%) on March 10th.

2. The spread between the 10-year and 3-month is now negative 113 basis points (-1.13%) vs negative 131 (-1.31%) on March 10th.

3. And the spread between the 30-year and 2-year is now negative 36 basis points (-0.36%) vs negative 103 (-1.03%) on March 10th.

Yields have steepened significantly over the last 10 days as investors begin pricing in the end of the Fed’s tightening cycle.

Why? Because banking crises are historically deflationary (recall the 1930s, Japan post-1991, and 2008).

This deflation increases the real value of debt while decreasing the value of collateral for loans (the Fed’s worst nightmare in our post-1980s credit-driven world).

Thus banks stop extending loans, effectively cutting off the supply of money and growth momentum. Asset prices at the margin begin declining. Risk-taking behavior flips into risk aversion. And this all feeds on itself into an amplifying feedback loop between slower growth, falling prices, and soaring real debt values (aka debt-deflation).

And this is why it appears the yield curve steepening will continue. Because the Fed’s already eased significantly since the SVB blow up. . .

The Fed Is Back To Easing As They Add Over $300 Billion To Their Balance Sheet

Since the SVB collapse and its ripple effects, the Fed has implemented ‘crisis lending’ programs to prevent further bank panics.

For instance, the Fed essentially re-opened the discount window (this is where the Fed makes liquidity readily available to eligible banks that need it). And created the BTFP (Bank Term Funding Program) which allows banks to sell assets at ‘par’ (aka full price) to the Fed in return for short-term (less than one year) cash.

This backstopping by the Fed’s a big deal because most of the assets sitting on bank balance sheets – such as mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and Treasuries – have declined in value during the Fed’s tightening.

Remember that when the Fed tightens, outstanding bond/asset prices drop.

So the BTFP allows banks to sell these assets to the Fed at full price – without realizing any losses/write-downs.

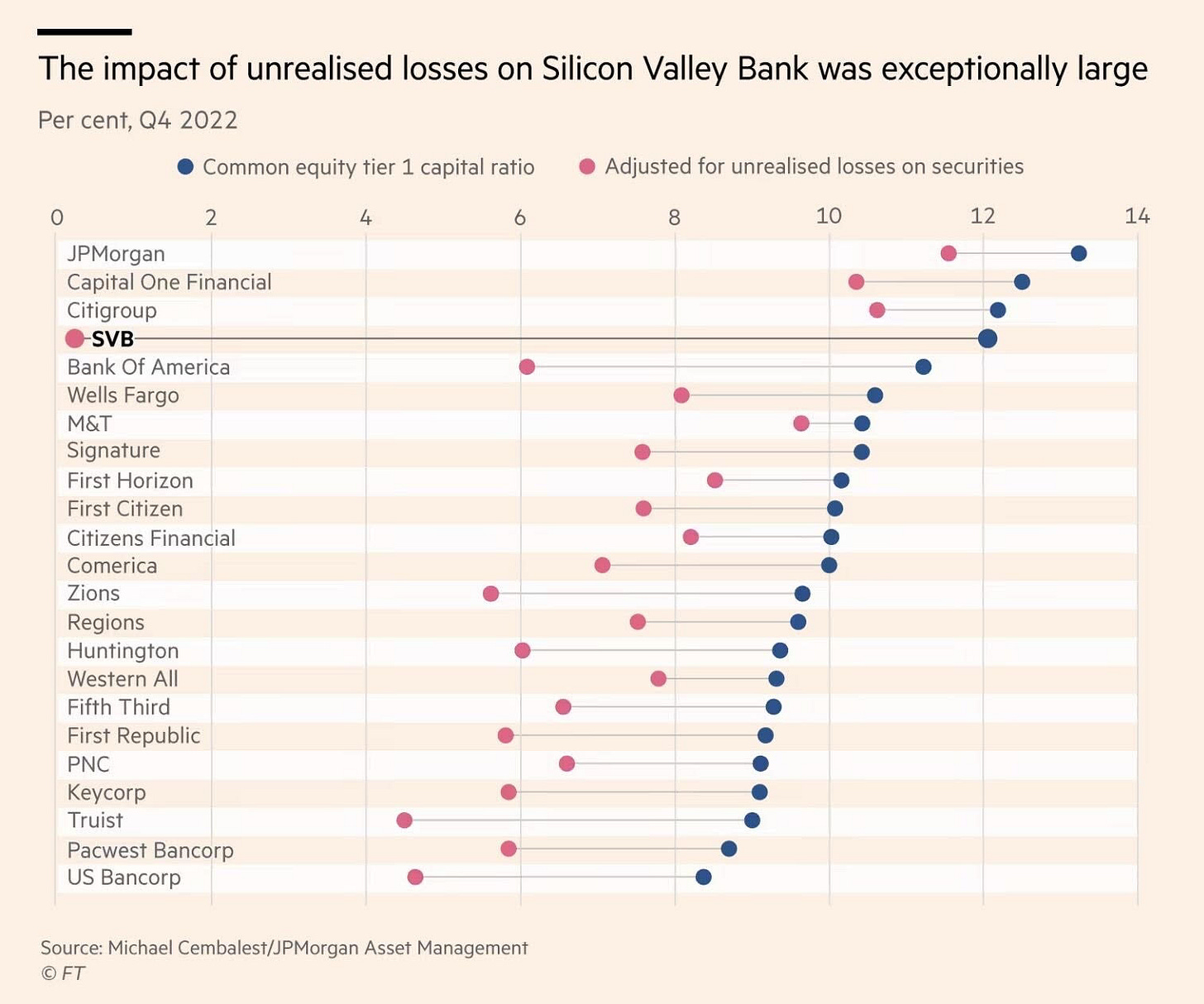

To put this into perspective, major banks are currently sitting on heavy unrealized losses. And if they were forced to sell on the open market (not to the Fed), they would see huge declines in their capital ratios (aka bank equity).

If these banks saw a horde of deposits come to pull their money out. And were forced to sell assets on the market. They’d be in big trouble.

So while many point at SVB, NY Signature Bank (SBNY), and First Republic Bank (FRC) – this is a systemic issue across the entire banking sector.

Hence why U.S. banks have already borrowed a record $165 billion from the Fed in a rush to shore up liquidity.

This is even higher than what was needed during the peak of 2008.

Meanwhile, the Fed and several other major central banks announced a coordinated effort last night to boost the flow of U.S. dollars in the global financial system. They’re using dollar-swap lines agreements with the aim of “keeping credit flowing to households and businesses.”

Keep in mind that swap lines are agreements between two central banks to exchange currencies. This allows a central bank to obtain foreign currency from the central bank that issues it (dollars here), and distribute it to commercial banks in their own country. Providing liquidity and keeping credit flowing.

All of this caused the Fed’s balance sheet to explode by over $300 billion in the last week (since they’re back to buying assets).

Thus – if the Fed continues hiking interest rates here – they’re effectively putting their foot on the brake and gas at the same time.

It wouldn’t make much sense.

And this banking crisis will only get worse with each subsequent rate hike.

This is why the bond market’s pricing in the end of this tightening cycle. Causing the yield curve to steepen as they anticipate rate cuts sooner-than-later.

Any potential of a ‘soft-landing’ went out the window as banks – especially the regional and community banks – struggle for survival.

Or said another way, any recession risk just amplified amid banking turmoil and the deflation it historically amplifies.

So – what’s next?

Time will tell if the Fed and major central banks can get things under control and shore up confidence in the financial system before it’s too late. But I remain skeptical.

Because as usual, investors are ahead of the curve. And central banks are behind it (proactive vs. reactive).

Meaning that they’re always too late to act.

And there’s nothing worse than being too late.