The Disappearing Pandemic Era Savings And Over-Leveraged Consumers Are The Seeds For Crisis

**This was originally published on SpeculatorsAnonymous.com

Almost every major pundit in 2022 believed a prolonged recession was around the corner.

But it never seemed to come.

At least not yet (as I’ll explain below). . .

Now, these same pundits believe that the U.S. economy is heading towards a “soft-landing” – aka a slower growth period that avoids a recession.

Their reasons? An extremely tight U.S. labor market – because of demographics – and the spend-happy U.S. consumer.

So, what’s a speculator to make of these seemingly bipolar pundits and markets?

Well – even though the data remains mixed – I still believe the economy’s unbalanced, fragile, and running on fumes.

Or putting it simply, we’re nearing a tipping point.

And that’s because consumer purchasing power is eroding – fast.

Let me explain why. . .

“Not All Savings Are Equal” – Most U.S. Consumers Have Already Bled Through Their ‘Excess Savings’

To give you some context: after COVID-19 struck in early-2020, governments around the world rushed to try and prevent any fallout. They pumped an obscene amount of stimulus into the system. And none more so than in the U.S. which injected some $5 trillion dollars into the economy – which was roughly 30% of 2020-21’s GDP (gross domestic product; the economy’s total size and output).

This money poured into households, small and big businesses, airlines, hospitals, local governments, and so forth.

Such government subsidies – like student loan payment pauses, mortgage foreclosure prevention, direct checks, PPP loans, and tax credits – were all used.

Why did they force all this liquidity into the economy?

Because it was textbook Keynesian policy – named after the early-1900 economist John Maynard Keynes – which stated that when consumers stop spending (save more), demand plunges and ripples throughout the economy. Thus the government must spend aggressively to offset any slowdown (Keynes called this the ‘paradox of thrift’).

So as governments feared another great depression – they aggressively spent to try and prevent one.

Or as Louise Sheiner – an economist with the Brookings Institute – said, “what the money did was basically make sure that when we could reopen, people had money to spend, their credit ratings weren’t ruined, they weren’t evicted, and kids weren’t going hungry. . . It’s a lesson that if you don’t want a recession to have really long-lasting bad effects you spend a bunch of money and you prevent it.”

All this delayed consumption during lockdowns and such a massive stimulus sloshing around both created ‘excess savings’ in households. With some estimates showing between $2.1 trillion and $2.7 trillion by the end of 2021.

And it helped Americans keep spending in the face of both higher inflation and higher interest rates.

No wonder the U.S. economy hasn’t slowed down yet. The consumer’s fully loaded.

But as always, when you spend more than you earn (which is what happened with many seeing negative real wage growth over the last year), it’ll eventually exhaust.

And that’s exactly what’s happening.

Americans have eaten away more than $1 trillion of their savings in 2022 alone – according to Matthew C. Klein – and if this pace continues, it’ll exhaust entirely by year-end.

Other estimates – such as from Goldman Sachs – believe households spent roughly 40% of their excess savings over 2022. And by late-2023 it will be down 70%.

What matters here is that even with differing forecasts of this ‘savings drain’ – it’s clear it’s declining.

But – I believe there’s an even bigger issue here.

And that’s the fact that all this excess savings wasn’t created equal.

Meaning that while total average savings are higher, the median sure isn’t.

U.S. households continue to grow further unbalanced. With the top 20% (which saw the most gains from the stimulus) continuing to spend their excess. And the bottom 80% running dry.

Mathew Rognile – an economics professor at Northwestern University – made this point clearly. “Deposits have been shrinking faster for the poorer depositors than the richer ones. . .”

And to put this into further perspective – in Q4-2022 – Primerica found that over 80% of middle-income households have either cut back on spending, or have dipped into their savings to cope with eording incomes.

Meanwhile – in the same period – lower-income families have already spent their surplus savings and are now forced to dip into their pre-COVID balances. And some 65% of Americans live paycheck-to-paycheck (9.3 million more year-over-year).

Keep in mind that as pandemic-era subsidies finally end, this will only increase financial stress.

For instance, student loan payments haven’t even resumed yet but may begin to as early as summer. And once they do – over 45 million consumers will feel a further $230-400 financial drain each month.

And more recently, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits ended last week – leaving roughly 42 million Americans without the extra $95-250 to spend on food.

As long as there were excess savings and all these government subsidies, it allowed consumers to spend. Keeping the economy growing.

Now, as consumers run dry – which’s roughly the bottom 80% of households – this will drag down overall demand as they save more (remember income is either spent or saved, not both).

But before demand plunges, there’s another way for consumers to keep spending.

And that’s through debt – which is historically never sustainable. . .

Household Debt Just Hit A Record High Of $16.9 Trillion As Consumers Needed To Subsidize Their Depleting Incomes And Savings

Over the last year, U.S. households have piled on a massive amount of debt.

According to recent NY Fed data, total household debt hit a record high of $16.9 trillion (up $2.75 trillion since the end of 2019). And non-housing debt hit a record high of $4.65 trillion.

And guess what the fastest-growing non-housing debt burden is over the last year?

Credit card debt.

Consumers have depended on borrowing more than ever to subsidize decades of anemic wage growth.

And while it fueled demand (more debt equals money creation and higher spending power), this always comes at a cost later.

And it seems that later is approaching sooner than many expect.

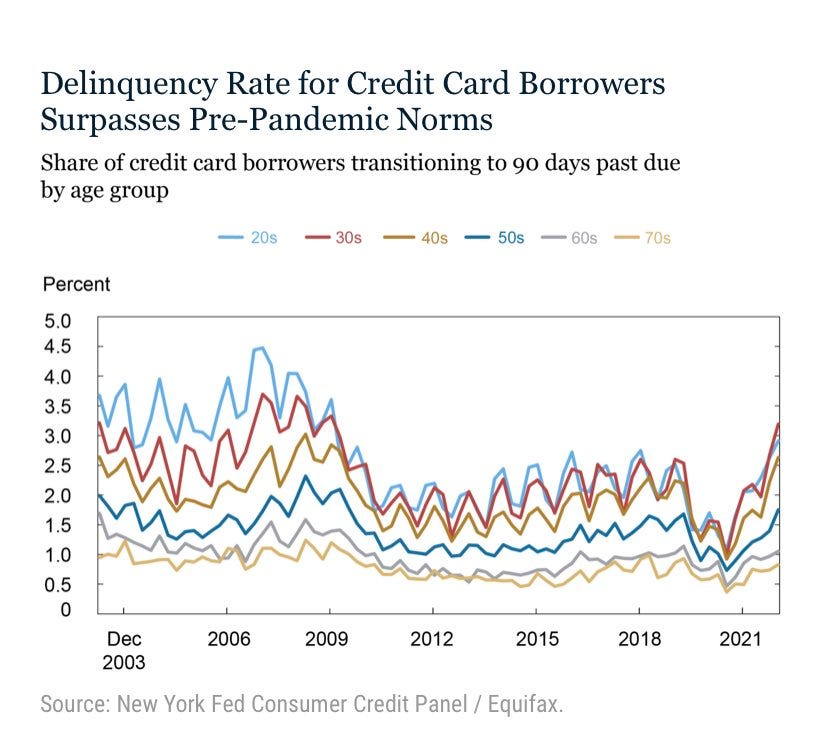

To put this into perspective – NY Fed data also shows that delinquency rates (90+ days past due) for 20-49-year-olds have surpassed pre-pandemic levels.

Actually, these delinquency rates are now at 2009 levels.

And auto-loan delinquency rates for the same age group are also back above pre-pandemic highs.

So while many are still making their debt payments, the rate of change of missed payments is accelerating quickly as purchasing power (excess savings) diminishes and debt becomes more expensive from higher interest rates.

And I believe this trend will continue – which increases economic fragility.

Beware The Risk Of Debt-Deflation As Over-leveraged Private Consumers And Markets Near A Tipping-Point.

As I’ve written before – it’s no surprise that this debt binge would inevitably inch closer to a tipping point.

There’re two reasons for this.

First – ever rising private debt loads will always become unsustainable when it’s dependent on anemic wages. Thus forcing consumers to eventually stop borrowing and focus on saving and paying down debt (deleveraging) instead.

This is a big issue we see after debt-fueled booms – like what happened in post-1991 Japan, post-2008 U.S. and post-2012 in the Eurozone.

Now, you may be thinking, “isn’t paying down debt a good thing?”

It generally is. But the problem is when everyone does it at once.

This is known as the ‘fallacy of composition’ – the error of assuming what’s true for an individual is true for an entire group.

If a handful of households deleverage, that’s considered prudent and ideal. But if every household begins deleveraging, that’s considered an economic black hole.

That’s why – in a credit-dependent monetary system like ours today – governments and central banks treat deleveraging as the plague.

And second – when debt-fueled asset bubbles begin declining, which has most often caused all of the big economic crashes in history.

Why?

Because once buyers leave a market (either from too high of prices or debt becomes too costly), prices peak. And eventually begin falling as marginal sellers take profits and get out.

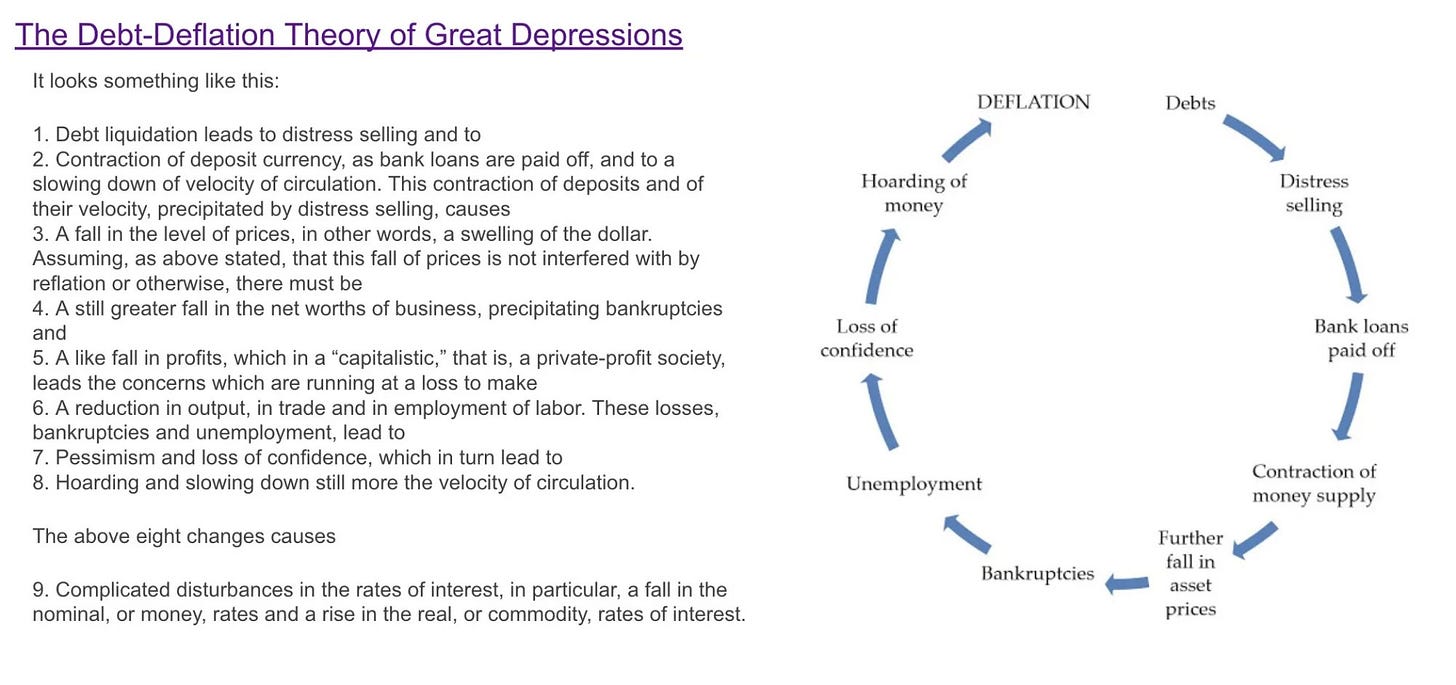

And this downward cycle feeds on itself because it’s an amplifying feedback loop. Meaning more selling begets lower prices, which begets more selling; repeat.

And this causes ‘debt-deflation’.

Debt deflation was a term coined by early-1900’s economist Irving Fisher. After he witnessed the debt-fueled implosion that triggered the Great Depression, Fisher theorized that depressions are due to the overall level of debt rising relative to falling asset prices and consumption. Thus fueling a feedback loop into further asset declines, rising unemployment, higher debt burdens, and on and on.

Thus both these reasons – rising debt relative to wage growth and declining asset prices – are reactions to an over-leveraged economy with anemic growth.

And as the U.S. government scales back subsidies and the Federal Reserve continues tightening, consumers will continue being squeezed dry.

So – in summary – the bottom-80% of consumers have seen their savings deplete rapidly over the last year as they try to stay above water. And have turned to huge amounts of debt to help them do so.

Governments have created extreme moral hazards and malinvestment with all their stimulus. Creating temporary demand and growth. But it will inevitably decline.

Like the relatively little-known Austrian economist – Murray Rothbard – said, “the greater the credit expansion and the longer it lasts, the longer will the boom last. . . Evidently, the longer the boom goes on the more wasteful the errors committed, and the longer and more severe will be the necessary depression readjustment. . . “

That’s why I’m not surprised we didn’t have a big slowdown or recession in 2022.

Because as long as there are excess savings, stimulus, and access to debt, the private sector can continue spending.

But – eventually – I believe they’ll hit a wall as stimulus, credit, and savings fade (which they are). And households must then cut back on spending and instead worry about paying down debts.

It may not be tomorrow. Or even in 2023.

But it will happen.

It always does.