Macro-Thoughts: Yes, Labor Markets Are Tight - And It's Because of a Demographic Crisis

February 3, 2023

Dear Speculators Anonymous Reader,

I hope all is well and that you're ready for the weekend.

I know it's been a long week with lots of big economic and market moves. So I will keep this simple.

All I want to share with you is why I'm not getting too caught up in the employment data.

And why I believe you shouldn't either.

Let me explain. . .

Macro-Thoughts: Yes, Labor Markets Are Tight - And It's Because of a Demographic Crisis

Today we saw a "blockbuster" rise in employment data - hitting 517,000 new hires in January (breaking out of the declining trend).

And while it was hot (most hiring coming from the leisure/hospitality, healthcare, and government sectors) mainstream pundits continue thinking the labor market rules supreme.

But I disagree.

That's because even though the U.S. unemployment rate is sitting at near historic lows, much of it is due to the huge demographic problems that continue plaguing the economy.

For instance - the U.S. labor force participation rate (aka the LFPR; the percentage of the population in the labor force) has continued declining over the last 23 years. Meaning that more people are leaving the labor force than entering.

In fact, it hasn't even gotten back to pre-covid levels. . .

Now, there are two big reasons the LFPR rose steadily post-world war two:

First, women were entering the workforce en masse.

And Second, the surge in births between 1946-64 (aka the baby boom) saw the only single upswing in the U.S. fertility rates in the last 220 years.

Thus this surge in workers pushed the LFPR up.

But keep in mind that every cyclical feedback loop will inevitably turn - and that's what we've seen since the late-1990s.

The number of women entering the workforce peaked, and the baby boomers are now retiring (aka leaving the labor force).

Meanwhile, U.S. fertility rates are sinking toward all-time lows (this trend was already amplifying long before COVID)

And this declining fertility rate is a global problem (especially in Europe and Asia). Because there aren't enough new young workers being born to subsidize the old, sick, and retired

But these are just a few factors distorting the labor data.

Here's the one I'm worried most about. . .

As of today, there are currently over seven million prime-age working men (25-54) sitting out of the labor force (these are known as "NILFs" - Not In Labor Force).

To put this into context, the prime-age male NILF's rate is 3.5x higher than its 1965 level.

Whether it's because of school, being a stay-at-home dad, or lack of skills - they're choosing to sit out.

Meanwhile, work rates for older Americans (55+) remain stuck at 2020 levels. And the growth in prime-age working women is now also looking relatively anemic (not even back to pre-CVOID levels with two million women sitting out.)

Thus today's manpower levels are roughly 4 million workers less than if the workforce had kept growing at its pre-COIVD trend (with 2.2 million retiring "early", and the rest between covid related sickness/deaths and weak immigration).

Now, many may think, "they'll surely come back, right?"

Well, I'm doubtful.

Because this is a demographic (social) issue, not an economic one.

For instance, why is there such an extraordinary imbalance in the demand for work and the supply of it? Where’s the equilibrium?

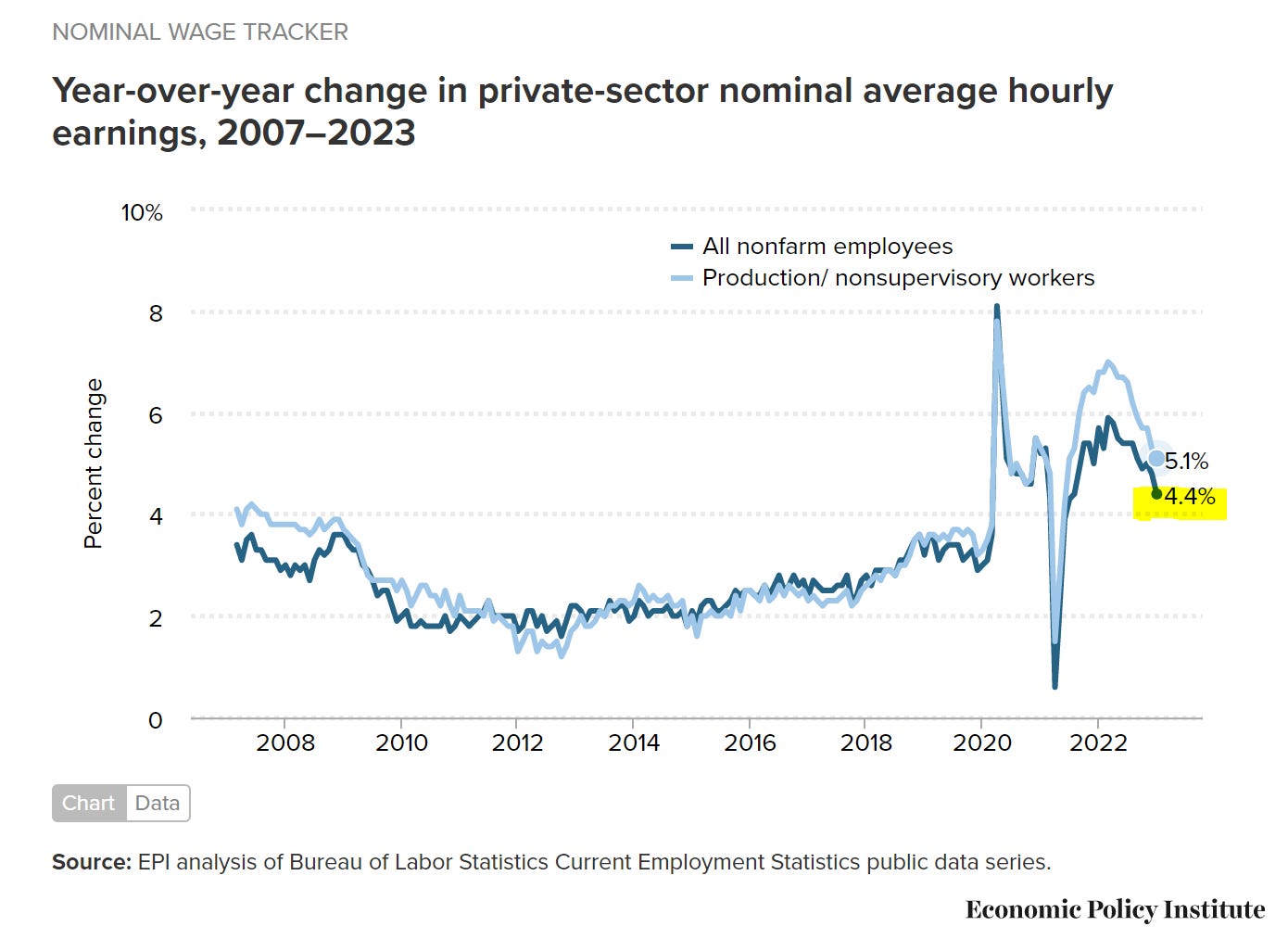

There are currently 1.7 job openings for each unemployed person. And wage growth has soared to multi-decade highs since 2020 and remained robust (albeit falling since, as I expect deflation).

If this was an economic issue, wouldn't more 'jaded' potential workers have jumped back into the workforce to soak up these job openings and much higher wages?

Yes, they would've. But that's not what's happening.

And this is what scares the Federal Reserve most.

Because if suddenly - let's say 3.5 million citizens - rushed back into the labor force, the unemployment rate would spike up as they looked for work.

But alas, it hasn't. And it doesn't appear it will.

Thus the labor market grows tighter and tighter. Where I expect it to remain for many more years (if not decades).

And while many pundits preach about declining demographics and the wage-price inflation it'll cause, I'm not convinced.

Two big reasons this causes deflation long-term:

Countries with demographic issues see greater automation to make up for the lack of workers (For instance: the world´s top 5 most automated countries in manufacturing 2021 are: South Korea, Singapore, Japan, Germany, and China - all dealing with negative and shrinking demographics). And greater technology proliferation is historically deflationary.

Tighter labor markets mean higher 'real' wages (adjusted for inflation). Meaning there's less aggregate consumption relative to output so prices fall at the margin (allowing wages to rise in real terms).

To put this into perspective, Japan's had an extremely tight labor market post-1990s (after their debt-deflation crisis) and their collapsing demographics.

And while the Japanese unemployment rate is now below 2.6% (left side of chart), inflation has stayed muted (besides periods of external shocks like higher energy prices) and they can barely eke out any economic growth (in fact, Japan's real GDP hasn't grown in about 20 years).

Next, take a look at the Euro-area (the19 countries) which also has fading demographics and an increasingly tighter labor market.

The Euro-area unemployment rate has fallen to 6.8% (left side of the chart), the lowest level since the data began compiling in 2005, and down 50% since the 2012 Euro-Greece crisis. Yet inflation has also stayed anemic (besides the 2021-22 energy price shocks) and they can also barely get any real growth (the Euro-area's real GDP has been flat for roughly 12 years).

It's important to realize that these fading demographic issues sap both growth and demand. Which is deflationary.

As we learned in economics-101, demographics + productivity = growth.

So, again beware of the pundits that preach higher inflation because of labor market tightness and accelerating growth from it.

Yes, could inflation break out? Of course. But I believe it's more cyclical inflation during a structural deflationary cycle (i.e. small spurts of price growth increases amid falling prices long-term).

And yes, there are big differences between the U.S. and the Eurozone and Japan - especially since the U.S. is a current account deficit-running nation while the E.U. and Japan run massive current account surpluses (I'll write more on this later as it's pivotal to understand global imbalances).

But I believe this will be the Fed's great folly: it is focusing so much on labor markets (that are tight because of demographics) and using monetary policy to try and move them - causing ripple effects throughout the rest of the economy. . .

Or said another way: they're trying to fix something that's a social issue, not an economic one. And the blowback will appear in other areas (such as greater booms and busts in asset prices).

Just some food for thought.

Other Content:

I published one macro article recently at Speculators Anonymous. If you haven't read them yet - please do.

How An Inverted Yield Curve Actually Amplifies A Recession As Banks Tighten Credit - many believe an inverted yield curve is an outdated tool. But that's far from true. In fact, there's more than enough empirical evidence that banks (who are the money creators in the economy) look at the inverted yield curve when deciding on lending standards. And as we've seen, there's been a massive tightening in bank credit in Q4/2022 which will weigh on U.S. growth.

Latest Book Recommendation:

Last year I read the thick tome -'The Rise and Fall of American Growth' by Robert J. Gordon' - and it's become easily one of my favorite books.

Although it's dense, it's a must-read to understand how productivity (Gordon uses 'total factor productivity' as his gauge; aka capital + labor inputs) in the last three 250 yearsdramaticallyexploded - greatly increasing living standards (especially during the 2nd industrial revolution - aka the great century - between 1870-1970).

You see, many only focus on thedemandside of the equation. But studying how supply chains and productivity evolved and developed is paramount to understanding prices (remember it's demandandsupply together).

And while the whole book is a magnificent walk down history, I believe Gordon's real important insights come at the end when he shows how since the beginning of the 3rd industrial revolution (post-1970s), total factor productivity hasplungedas we've seen increasingly diminishing returns in production (besides the info-tech and digital sectors).

For perspective: productivity isless than halfwhat it was in the 1870-1970 period.

He makes the argument that these 'great inventions' could only be made once and proliferate throughout the economy once

For instance, the vehicle was made in the early-1900s and was a boon for growth and living standards. It connected the rural-to-urban economies and led to a wide-ranging ripple-effect of demand - such as roadside stores, diners, deliveries, highways, etc. But over time as this new tech proliferated, eventually, everyone had a car. And although cars today are superior, they're just nicer cars with more efficiency. They don't create a boom in productivity like when the first car was made.

This is just one example. And there are many more he goes into.

His thesis is important - especially in today's world as we've seen total factor productivity remain anemic and living standards peaked (now even declining).

I highly recommend it for economic/market history students.

As always - thanks for reading. And take care.

If you have any questions or comments - you can Contact Us here at our site. And make sure to follow me on twitter: @RadicalAdem

Thanks For Reading,

Adem Tumerkan,

Editor, Speculators Anonymous

Seems like Jeff Snider has been saying this all along. This is a simple explanation for an extremely complex topic. 🍻