How An Inverted Yield Curve Actually Amplifies A Recession As Banks Tighten Credit

Back in August, I wrote about the deeply inverting U.S. yield curve and how it indicated deflation and slowing growth ahead (which is what we’ve seen).

But – since then – I’ve seen media pundits shrug off any further downside.

Or as it’s popularly termed now, “the economy is heading towards a soft landing.”

I’ve seen respected analysts and pundits say things like:

“Yield inversion doesn’t indicate anything anymore.”

Or that, “in an era of quantitative easing (QE), inverted curves matter little.”

Or my personal favorite, “this time will be different.”

And while that is definitely a possibility, I believe there’s far more downside than many expect.

And so does the bond market – which is even more inverted than it was five months ago.

That’s why I urge you to beware of such disregard for the yield curve. Because it’s a very important signal for economic health, market expectations, and bank lending.

Let me explain why. . .

What’s Causing the Yield Curve to Turn Completely Up-Side Down?

For starters, to know why the yield curve inverts, one must understand why it does in the first place.

To put it simply, it’s when the bond market (which controls the longer end of the curve) is at odds with the central banks (which control the short end of the curve).

For instance, inversion happens when a central bank forces up short-term rates (such as when the Fed hikes the discount rate).

The Fed will raise these short-term rates when it believes the economy’s growing and inflation is picking up. And they’ll cut rates lower when they believe the opposite – that the economy’s fading into recession and deflation.

So it’s no surprise why the Fed’s currently tightening at its most aggressive pace in decades.

In fact, on a rate-of-change (RoC) basis, it’s the fastest rate-hiking cycle in modern history.

Why? Because inflation and growth were running very ‘hot’ from all the stimulus post-COVID.

Thus since early 2022, the Fed’s been pushing interest rates higher while also trying to suck reserves out of the banking system through quantitative tightening (QT) to try and cool things down.

But as the brilliant economist – Hyman Minsky – taught us, such sudden changes are the seeds for future crises and volatility.

And that’s why bond investors are calling the Fed’s bluff that it has this tightening cycle under control.

Or put another way, the bond market doesn’t believe that the economy will land as softly as the Fed expects. Nor will inflation slowly fade away, but rather plunge into deflation. So speculators begin thinking ahead, believing that such aggressive tightening will breed a future recession.

Hence, they’re buying longer-dated bonds to lock in those higher yields today since they fully expect the Fed will begin cutting rates sooner than later (when it will have to fight a deflationary recession that it’s caused).

That’s what an inverted yield curve tells us. That the bond market’s pricing in slower growth, deflation, and a recession.

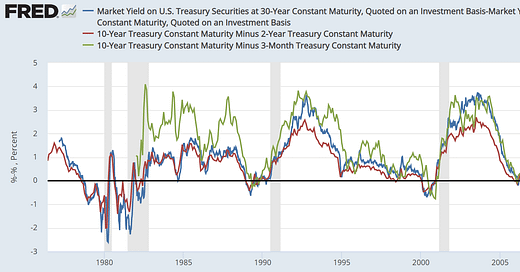

And it’s a powerful signal since it’s preceded the last eight straight recessions since the 1970s. . .

So – how does the curve look today?

Well, it’s completely upside down (meaning its deeply inverted).

For instance:

1. The 10-year vs. the 2-year spread is negative 70 basis points (-0.70%) – its most in decades.

2. The 10-year vs. the 3-month spread is negative 125 basis points (-1.25%) – its most in decades.

3. And the 30-year vs. the 2-year spread is negative 64 basis points (-0.64%) – its most in decades.

What this means is that the bond market is willing to collect smaller yields when making longer-dated loans – which many consider ‘irrational’ (why collect less yield for greater long-term risk?).

But it isn’t irrational. It’s roundabout (aka focusing on future policy changes rather than current ones).

Why? Because the Fed is reactive, and the bond market is proactive.

And that’s a major difference.

An Inverted Yield Curve Leads to Slower Growth? Yes, History Shows it Does.

Now – historically speaking – in the last eight recessions, an inverted yield curve led by about 12-16 months on average.

But it always followed.

And there’s a good reason for this. . .

Because banks look at the yield curve as a crucial leading indicator for economic health.

So as the yield curve sinks into inversion, commercial banks tend to tighten lending standards (aka curtail credit).

And this is exactly what we’ve seen across all major areas of credit extended by banks as yields invert.

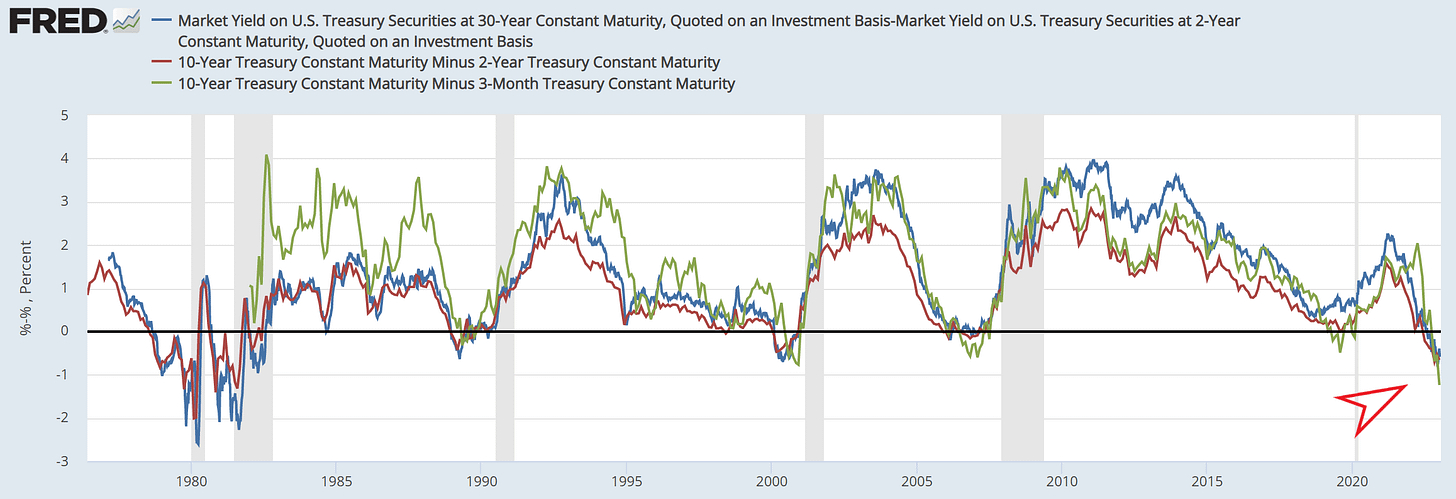

Take a look at the chart below showing the last 30 years of the 3-month vs. 10-year spread (light blue line – right side) compared to the net-percentage of banks tightening standards for business loans, credit card loans, and auto loans (left side).

Keep in mind that above zero means more banks are tightening loan standards; and vice versa for easing loan standards.

As it shows – historically – inversion leads banks to tighten credit standards.

And that’s exactly what’s happening as of late. . .

For instance – in just the last quarter (Q4-2022) – the percentage of U.S. banks tightening credit rose to:

40% for commercial and industrial (C&I) loans to medium-and-large sized firms.

32% for C&I loans to small-sized firms.

19% for credit card loans.

And 2% for auto loans.

These are all significant jumps in tightening standards – especially when compared to the same period last year.

So why do banks curtail credit once yields begin inverting?

The St. Louis Federal Reserve wanted to know this also and did a big study asking banks this very question a few years back.

And many surveyed indicated that even during a “moderate inversion of the yield curve”, they would tighten lending standards or price terms on every major loan category.

The potential reasons given were that:

1. Curve inversion indicates a less-than-favorable economic outlook (greater uncertainty as they expect slower growth and asset deflation).

2. Curve inversion will cause their banks to shy away from making riskier loans (aka become more risk averse).

3. And that curve inversion could cause loans to be less profitable relative to their costs (since they generally borrow short and lend long, inversion will cripple this).

Thus if inversion leads to further bank tightening (which it historically does) – that means it would indirectly cause the economy to slow.

This indicates that the inverted yield curve isn’t some ‘useless’ signal to ignore regarding a recession.

But it may actually amplify the cause of one. . .

Remember: Commercial Bank Lending is Key for Economic Growth – Both in Boom and Bust.

Many aren’t aware that commercial banks extending credit are what fuel money creation, liquidity, and amplify the business cycle.

So as banks tighten loan standards, this weighs down all three.

And in the post-1980s credit-driven world, that’s a big deal.

A common misperception by economic pundits is that banks lend based on interest rates. That’s why they believe when the central bank cuts rates, it’s what stimulates lending.

But this isn’t actually correct.

Because – in practice – banks lend based on confidence that the loan will be repaid and confidence in the liquidity of other banks and the system as a whole.

And once that confidence becomes shaken – they begin curtailing credit. Which has a negative ripple effect on the economic system as a whole.

Now – looking at the past – banks begin curtailing credit in the later stages of a tightening cycle.

Thus I believe there’s still further downside ahead. . .

So – in summary – beware of those claiming that an inverted yield curve is now useless. Or that “this time will be different.”

Because it’s still more important than many care to realize.

*Note: for more insight into how the modern banking system works, I highly recommend ‘Where Does Money Come From?’ by Werner, Jackson, Greenham, Ryan-Collins. It’s an easy-to-read guide on how the modern monetary system works and why credit creation is so important. It’s a must-read in the Speculators Anonymous: Reading List.

**This article was previously published on my site at Speculators Anonymous