A Global Earnings Recession Looms And Zombie Companies Are The Most Fragile

Back in October, I wrote about the looming global earnings recession.

And while the media’s busy focusing on the world’s banking issues (which will only amplify any economic downside), the earnings situation hasn’t gotten any better.

Actually, it’s much worse.

But before going on – what exactly is an earnings recession?

Simply put, it’s when corporate profits across major sectors fall year-over-year for two or more quarters.

So, while global demand keeps dropping and world trade declines, it appears an earnings recession is baked in.

But it’s not.

Even in the face of disappointing earnings and tighter credit conditions, the S&P 500 Index (SPX) is now trading around $4,000 – up 8% since October.

It’s clear that the crowd’s discounting any further earnings weakness.

But I believe this is overly optimistic. And that major leading indicators show there’s an earnings recession inching closer. And this will be much deeper than many realize as there’s a wave of zombie firms that cant risk lower profits.

Let me explain. . .

Sinking South Korean (And Global) Exports Signal A Global Earnings Recession

South Korea is the fourth largest economy in Asia. And the seventh largest exporter in the world (according to merchandise values as of 2022).

Hence why it’s important to follow their trade data and economy.

So, what are South Korean exports telling us about the global economy now?

Well, things are looking bad. And especially so as-of-lately.

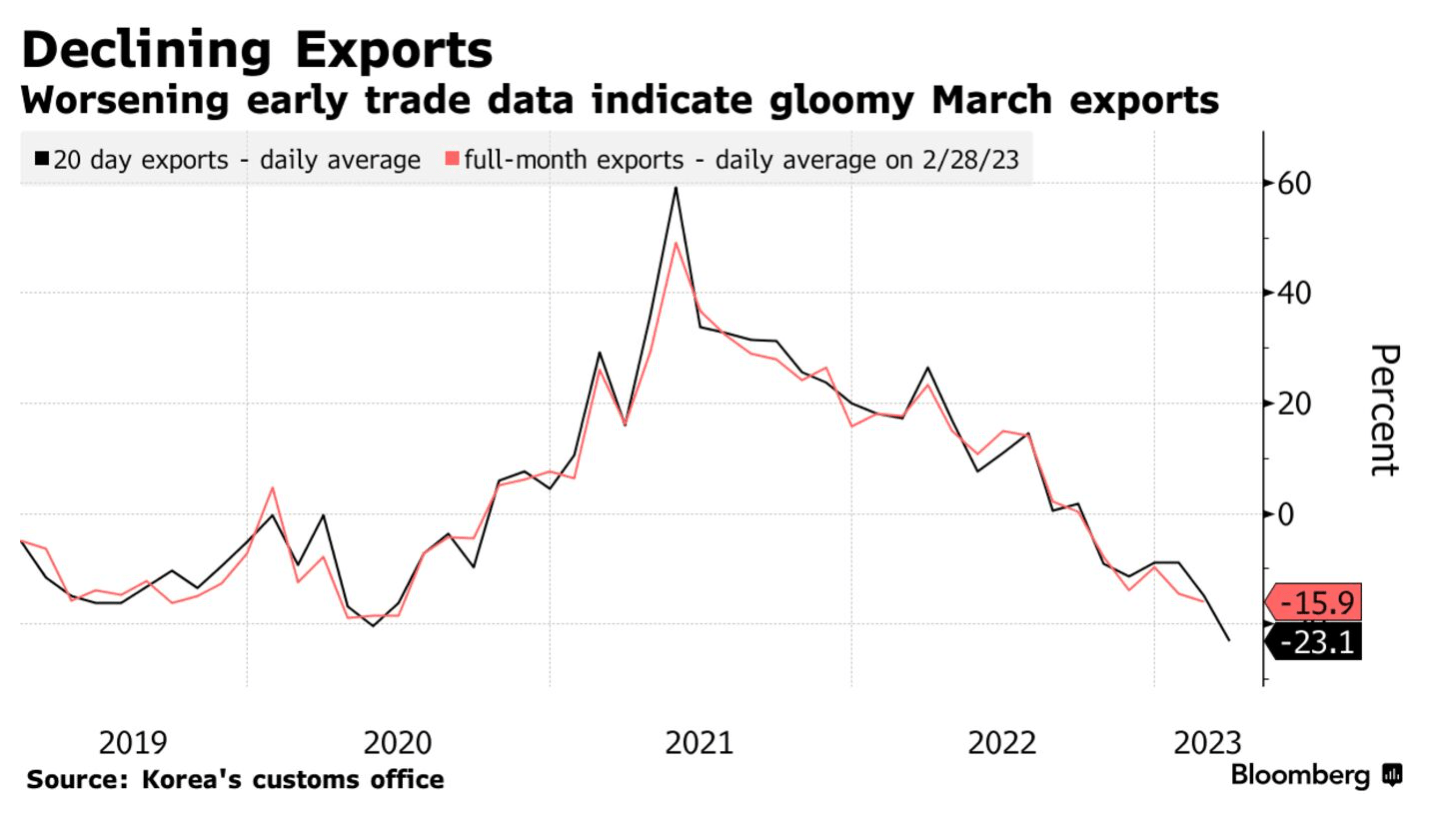

To put this into perspective – early trade data (the first-20 days of March) show South Korean exports dropping 23.1% year-over-year.

This is the lowest it’s been since peak-COVID in early 2020. And it looks to drop even further.

Making matters worse, shipments to China – three months after “re-opening” – have plunged 36%.

In fact – among the top 10 export destinations – the US was the only one that showed increased demand for Korean exports (a measly 4%). Meanwhile, shipments to Vietnam dropped 28%. Hong Kong down 45%. European Union down 9%. And Taiwan plunged 53%.

Such large drops in South Korean exports indicate that consumers and businesses around the world are cutting way back on spending.

Keep in mind that South Korean exports were already in decline before the recent wave of banking crises. Which will most likely weigh on demand further.

And this isn’t bullish (good) for global corporate earnings.

Why? Because there’s been a tight correlation between South Korean export growth (ala SKEG) and corporate profits over the last 30 years.

Thus when the SKEG moves sharply one way or another, global earnings usually follow close behind it (with a 12-month lag).

Or – said another way – if South Korean exports increase, so do global earnings. And if they decrease, earnings decline.

Now, it may sound odd that global earnings seem to follow South Korean exports.

But it’s true.

That’s because South Korea supplies the world with a wide variety of goods and is a major hub for international trade activity.

This makes South Korean export growth (aka SKEG) one of the most important – if not the most important – leading indicators in the world.

To put this into perspective, just take a look at annual SKEG (blue) vs. annual U.S. corporate profit growth (red) since 1990.

And even though this is only U.S. corporate profits and not global, there’s a clear causal chain here.

While there are year-over-year base effects in play – it’s the rate of change (RoC – aka momentum) that matters most. And it’s collapsing quickly.

Thus if this correlation still holds (which I believe it does) – then look for a deep global earnings recession over the next year.

And while South Korean exports are a historically reliable indicator of growth and corporate earnings, one could argue it’s a “one-off.”

But it’s not just South Korea that’s seeing sinking exports – it’s the rest of the world.

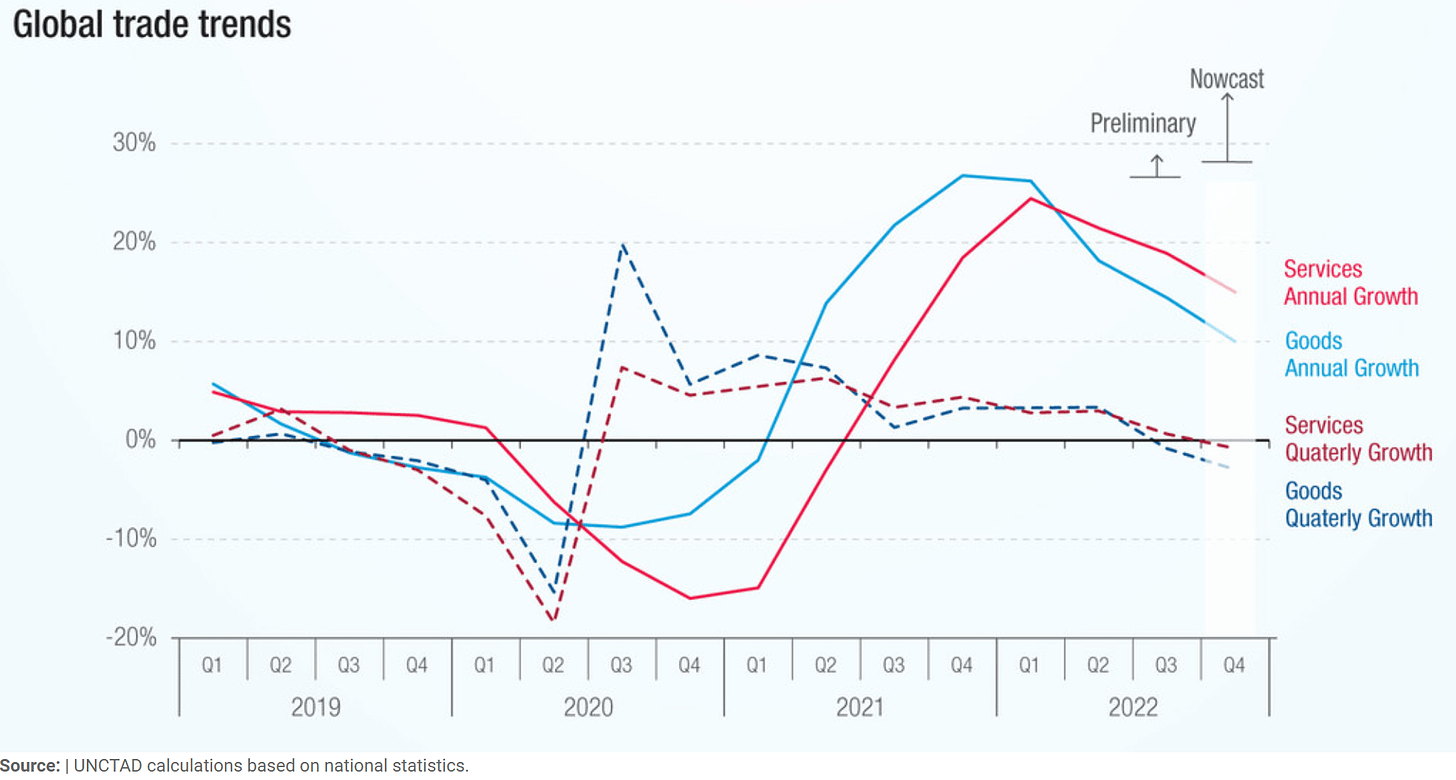

According to the United Nations Trade and Development agency (UNCTAD), global trade growth turned negative in Q3-2022. And is expected to continue its decline over 2023.

UNCTAD said that “geopolitical frictions, persisting inflation, and lower global demand are expected to negatively affect global trade during 2023.”

After studying the anemic world trade data, it’s not hard to see that any upwards momentum has faded. And things are now in decline.

In fact, the sinking trade data increases the probability that the SKEG indicator will be correct yet again. Further reinforcing my hypothesis of a global earnings recession

And expecting worldwide trade growth to pick up from here just isn’t likely. Especially in the face of higher costs, tighter monetary policy, anemic consumers, and now banking crises.

The Market Isn’t Pricing in An Earnings Recession – Creating A Potential Contrarian Opportunity

So, global earnings look pretty ugly here.

And yet, the crowd’s discounting a significant amount of downside.

Or rather, the crowd isn’t pricing in much of an earnings recession at all.

To put this into perspective, the Morgan Stanley non-manufacturing leading indicator (one-year lag) – which has been fairly accurate for two decades – indicates a 25% decline in S&P 500 earnings over 2023.

This is substantially lower than the current consensus (crowd) expectations.

And thus creates a contrarian opportunity. . .

Markets are busy fixating on the Federal Reserve pausing its tightening cycle after the recent bank runs (read more here). Thus they’re expecting some potential stimulus from a pause and bank bailouts. (Or rather, increased global liquidity spillover from the emergency lending programs).

But even with anemic global growth, weak earnings, and banking issues – central banks are still tightening.

Imagine, then, how stretched and fragile things are becoming as the largest central banks in the world – such as the Fed, the ECB, and the BoE – all continue tightening.

Adding to the mess, higher interest rates put pressure on corporations dealing with massive amounts of debt.

But none more so than those already with anemic earnings prospects – such as ‘zombie’ companies.

The Living Dead: A Wave Of Zombie Firms Will Be Squeezed Most By An Earnings Recession

Putting it simply, a zombie company is an uncompetitive business that’s only kept alive because of cheap debt.

Or said another way, zombies essentially don’t make enough money to repay the principal (only interest) and thus constantly require new debt.

A good measure to determine a zombie is if a firm has lower than a two ‘interest-to-coverage’ ratio (ICR). Meaning the profits needed to meet interest expenses (the higher, the better; vice versa).

And while there’s conflicting data about zombie firms, Goldman Sachs recently estimated that some 15% of U.S. listed companies “could be considered zombies.”

Meanwhile – according to Bloomberg – there are over 620 zombie firms in the Russell 3000 Index.

That’s over one-fifth (21%) of the entire index.

Making matters worse, The Economist highlighted that some one-fifth (20%) of the total debt ($4 trillion worth) held by U.S. and Euro-listed companies are firms with an ICR of less than two.

They also added that – according to the Fitch rating agency – roughly 60% of the investment grade non-financial corporate bond market is now rated triple-B (BBB). Which is just one step above a junk rating.

This puts many firms (and creditors) in an extremely fragile position.

Thus if earnings continue to fade – and interest rates stay elevated – these firms will be squeezed. And many will most likely fail, rippling through credit markets and the economy.

So – in summary – sinking South Korean exports point to a looming global earnings recession over the next year. And as of now, the market is currently discounting this possibility by a wide margin.

There’s a wave of zombie firms – which are already fragile to begin with – that can’t handle lower earnings. Especially at a time when credit’s tightening.

Either way, the momentum continues fading for cashflows.

The fallout from the recent banking crises hasn’t even rippled through yet. But I expect this will only add downside momentum to the global economy.

And remember, this earnings recession was already well-underway before the current banking issues.

Beware.